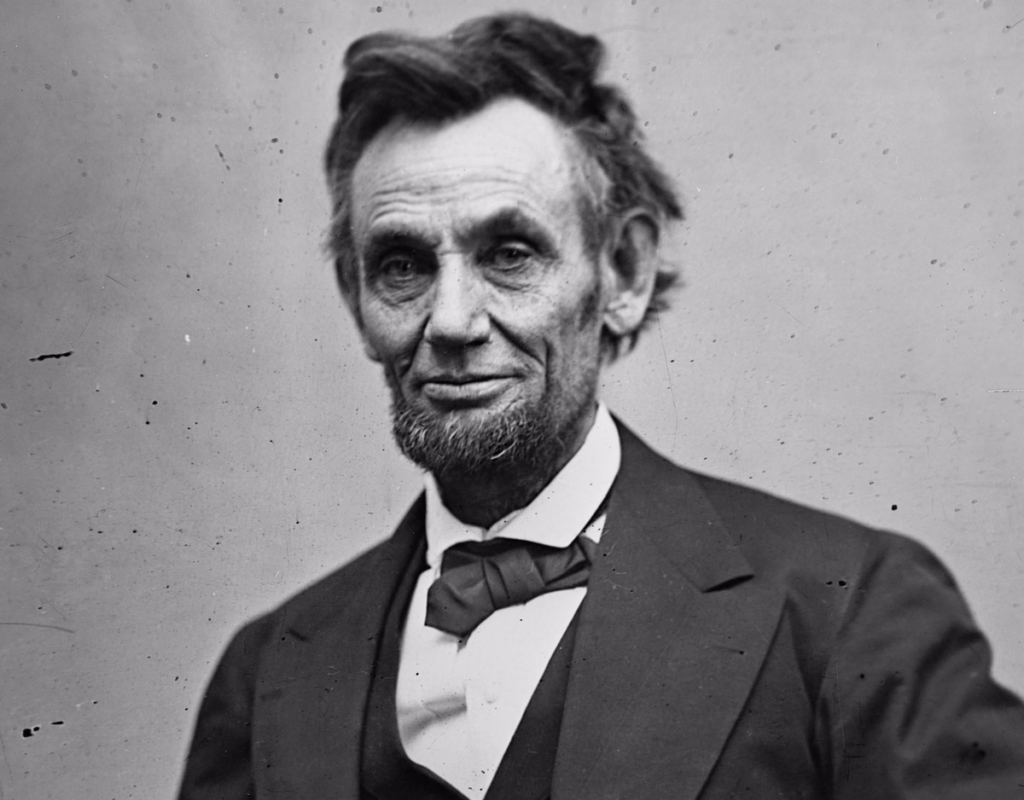

Honest Abe made bed-head look good.

Before speeches were written by committee

The most famous speech in American history is only ten sentences long. Reading it aloud as part of civic ceremonies or school activities is a near-universal shared experience.

I myself recited the speech in front of a huge crowd of veterans back in high school. The wind blew my only copy off the pedestal and I had to finish reciting it from memory. Poorly, as it turned out. You never forget butchering Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.”

Read it yourself:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

My own chilly reception was in good company. Few who were present for the actual speech in 1863 thought it was very memorable either. Lincoln was fighting off a minor bout of smallpox that day and by all accounts was underwhelming in his delivery.

It didn’t help that earlier in the day the Hon. Edward Everett had delivered a bombastic two-hour long recounting of the battle, moment by moment. Everett was the headliner, and Lincoln was scheduled to give a few “remarks” afterward. The crowd was all crickets after the speech ended, though accounts differ as to whether it was an awed hush or respectful silence. Republican newspapers thought it was great, Democratic ones thought it wasn’t, and foreign newspapers similarly thought it laughable.

That li’l arrow there is pointing to Lincoln. Apparently.

But They Were Wrong

Over time, Lincoln’s short speech grew dramatically in impact and importance. It was reprinted in history and civics textbooks and frequently recited on national holidays. Martin Luther King Jr. referenced it in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The Constitutions of France and Japan translate Lincoln’s phrase “government of the people, by the people, and for the people” directly. President John F. Kennedy loved the speech so much that he patterned multiple of his own after it.

The “Gettysburg Address” was a powerful message, but it didn’t necessarily seem like it at the start. A lot of powerful messages are like that. When you find the message that is true to you and your work and powerfully relevant and motivating to your clients, it may also seem like it doesn’t resonate at first. The most powerful messages grow with time–but they also need time to grow.

If you know you’re saying the right thing, don’t give up. You may not see results in the first weeks or months. A truly motivating message pays off in years. And for many, many years to come.

If you don’t know whether you’ve got the right message, give us a call. We can help with that.